My friend David and I took an epic road trip many years ago, the kind that can only be made by the young and foolish: Chicago to New York to surprise a friend. With no more than $20 in our pockets and his grandfather’s gas card to cover expenses, we set out to the east with the sun at our backs. Oh, to be 19 again.

Food? We had the gas card. Hotels? I don’t think it ever occurred to us. It was only a 12-hour drive, after all. At a truck stop convenience store around South Bend, Indiana, we gassed up the tank and stocked up on provisions. Jerky. Chips. Water. Nuts. And, as a last impulse that can only be ascribed to … could there be an adequate explanation? … a roll of bake-at-home cookie dough.

Raw cookie dough. Delicious, filling and funny—it seemed like a great idea. Bake, schmake! So as we drove we passed the plastic tube to take bites of dough. By the time we hit Youngstown, Ohio, neither of us felt so well. By the State College, Pennsylvania, cutoff, our bellies were aching like we had eaten billiard balls. Now I realize there was a lesson for today.

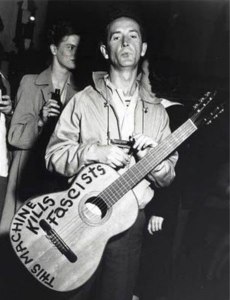

With the memory of that gut pain as my guide, I say we need to find a new place to share half-baked ideas and raw notions. In the spirit of show your work and working out loud (#WOL), we need a renewed sense that there is value in sharing the half-baked, ill-formed and in-progress stages of our work.

Just as luck finds those who prepare, serendipity of ideas and connect ing disparate dots into new insights come to those who are willing to share not only products but process; not only results but notions, hunches and hypotheses.

ing disparate dots into new insights come to those who are willing to share not only products but process; not only results but notions, hunches and hypotheses.

The reason why many “digital age” companies try so hard to create open spaces for folks to bump into each other—think Google’s cafeteria, Nike’s athletic facilities, cubeless open workstations and Yahoo!’s effort to curb its remote workforce—is to create the conditions for serendipity to occur.

Even when we are not actively collaborating with each other, we should certainly be cooperating with each other, dovetailing our efforts and forming brief spats of collaboration toward the same goals.

Short of the Google cafeteria (or, in addition to it), what this calls for is a more transparent, open spirit of sharing and learning. When you wait until your work is fully baked, with all the icing applied, you’ve waited too long. The learning, the idea development, the benefit to others from your work are revealed in your process, not your product. Mistakes and wrong paths are the quintessential learning moments.

Don’t wait to share your plate of beautiful cookies. Show us your ingredients—how you crack the eggs, the messes on the counter, why you chose your bowl and tools—and let us decide what to do with the dough. Some of us will bake it; others prefer it raw. That’s where the learning happens.

#WOL #LOL #ShowYourWork