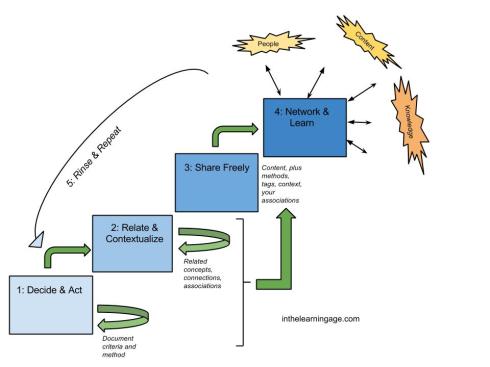

It’s triangulation time again! Three distinct sources I’ve filtered through in recent weeks have started to connect in an unexpected way, and I think it’s time to explicitly connect them here. It’s Personal Knowledge Mastery (PKM) in action: filtering, sense-making, connecting, sharing.

Item #1. An NPR story about the experience of heroin addicts during—and after—the Vietnam War. The incidence of drug abuse was high for GIs in Southeast Asia, and there was a real fear they would return to the U.S. to become hundreds of thousands of addicts on the streets of our cities.

But that’s not what happened, and it rocked some fundamental thinking about the nature of addiction and habitual behavior. In fact, only 5% of heroin users continued to abuse the drug after they returned home. What researchers found is that context plays an enormous factor in habitual behavior. Once the context of the battlefield conditions was removed and soldiers returned to civilian routines, heroin use plummeted even where access to heroin was still relatively easy. Lesson #1: Context is key for habitual behavior.

Item #2: A CMS Wire article on building high-performing learning organizations came to me via my scoop.it feed. Business Consultant Edward D. Hess identifies three conditions for building high-functioning learning organizations: 1) the right people; 2) the right environment; 3) the right processes. I encourage you to read the short article, but the takeaway is that a context of innovative culture paired with intentional practices creates the conditions for high-performing learning. Lesson #2: Context needs to be paired with the right tools and processes.

Item #3: I came across a short interview with George Siemens, the godfather of Connectivism, in which he was asked to reflect on MOOCs and their efficacy (or lack thereof). His main thesis is that MOOCs deconstruct the traditional hierarchy of classroom learning {Teacher –> Content –> Students} into a network of learning in which the teacher “is a node in a network, among other nodes. They might still be a very important node, but students can learn from [other sources and each other].” In this case, the teacher needs to pay more attention to the context of learning, ensuring that the students “have the skills and capacity to learn in a networked way … to build the right kind of critical thinking skills.” Lesson #3: Network learning is a new context in which people need to learn a new set of habits.

I was asked recently to speak about how I might build an effective learning program among a geographically and culturally diverse set of learners. Without consciously drawing on these three lessons explicitly, my approach built on them.

An individual is centered on her specific skills and knowledge. Those are what create her sense of self and value to her organization. Outside of that is a layer of her measure against others and against the needs of her position. That is, her competency and her assessment of that competence against requirements and expectations. In order for her to feel growth, opportunity and fulfillment, she needs a way to map her knowledge and skills to design a path of professional growth that aligns with the needs of the organization. Lastly, the outermost layer is the context, mindset and habits (together, that is culture) that allow her to make sense of new information, add her own value to it, and share it back out to her network of other learners. This is PKM in action.

Through the PKM lens we are able to both glean more productively with our learning cohort or formal community of practice, and form the skills and habits to learn from our constantly shifting professional learning network (PLN) – that network of nodes (people and information) that form the context of personal and organizational learning.

These three layers — workplace learning’s own rule of three — all need to be in place so that both individual and organizational learning happen.